We were on a little Sociology of… break due to my travel schedule and the election, but as a palate cleanser, it’s time for another edition of the periodic round-up of My Current Cultural Diet. As noted in Vol. 1, these items are largely unrelated, but they do touch upon other Sociology of… topics we have covered or will address in the future. I hope something in here is of interest and sparks some conversation — and, as always, I welcome your thoughts in the comments.

Articles

“Does Anyone Really Know You?” and “In the Age of A.I., What Makes People Unique?” by Joshua Rothman

You don’t have to be an emo teenager to feel like no one really knows you. In the first of two recent New Yorker articles by Joshua Rothman, he ponders whether anyone really knows you: “What, exactly, is there to know? And who are you, anyway?” Does feeling known correlate with someone knowing a certain volume of details about your life? Or is it about knowing a specific information subset about you? Or perhaps, more esoterically, is it not about knowing “information,” but rather intuitively grasping your “essence”? And even if we tell people the details of our lives, does selective hearing allow them only to know the person that they want to know?

The sociologist Erving Goffman argues that we all wear masks, revealing different faces to different audiences in our lives. The masks are not false selves, however, but rather facets of our multi-dimensional personalities, underscoring that we are complex and often contradictory creatures. In both my academic teaching and public lectures, I find that people bristle at the suggestion that we wear masks. That somehow a mask isn’t authentic because it’s “hiding” something. In reality, we simply can’t be known to everyone in every way all at once. Even to ourselves. Masks are a necessary coping mechanism, and smooth(er) societal functioning relies on it.

Where does technology fit into all of this? Does it enhance or hinder our ability to be known? We all curate the information about ourselves that we post and disseminate online, serving as the architects of our public personas.

Identity formation and expression asks two core questions: 1) how do I fit into the group and 2) what distinguishes me from the group? We might now add a third category: What distinguishes us from A.I.?

Two dominant A.I fears center on its ability to replace humans in various jobs, as well as the disheartening reality that many college students — often paying exorbitant fees to be there — increasingly rely on A.I. to do their work for them. (I can make the long term case for the former, but the latter will always depress me.) What we don’t hear about enough, however, are the risks of dehumanization from A.I. — which is Rothman’s focus in his second essay, posing the question, “What, exactly, are humans good for?”

Two main “skills” come to mind: Love and creativity, both of which are often as painful and difficult as they are beautiful. The challenges they pose are part of what makes each so exquisite and contributes to their value. As A.I. gains the convincing ability to profess love and display artistry, we should proceed with caution, asking not only what the technology offers, but what it strips away.

Does A.I. make us more or less known? Can we ever be known if our interactions increasingly take place not with other fallible fleshy beings, but with technology? Ultimately, we must decide: Do we want messy and real or predictable and fake?

Books

Imminent, by Luis Elizondo: Please believe me when I tell you I was genuinely neutral on aliens before reading this book. But after…. Well, it’s hard to focus on anything else. Elizondo, a senior intelligence official, lifelong public servant, and former head of the Department of Defense’s Advanced Aerospace Threat Identification Program, does an excellent job of explaining how he also went from comparably neutral to oh-my-god-this-is-real-now-what?

I found myself shocked by the decades of information gatekeeping and the resistance by the Air Force and various religious military leaders to cooperate with these investigations. The mere fact that some of this material and evidence ever made it into traditional peer reviewed academic journals is remarkable — and further supports how worthy of serious thought it all is.

He is perhaps most compelling when he brings in the expert analysis of physicians, scientists, and engineers — none of whom are particularly interested in UAP, but who cannot explain the occurrences using even the most sophisticated scientific tools and theories — except using quantum physics, including the theory of relativity and quantum entanglement.

Trust me: I know it might sound crazy. But I would encourage you to read it and draw your own conclusions. Once you accept the laws of quantum physics, the information and evidence obtained by the government — largely over the last 80 years — seems more serious than spooky. These encounters and phenomena beg us to reckon with so much we don’t yet understand, not only about the universe, but about our own brains and bodies. Like Sebastian Junger in In My Time of Dying (which I mentioned in Vol. 1), Elizondo is not preaching philosophical or spiritual platitudes. Whether we are exploring near death experiences (a la Junger) or UAP, these “mysteries” that span millennia and pervade cultures all converge in quantum physics. It’s easy to become so drunk on our own perceptions of intellectual superiority that we forget that just because we don’t understand something, doesn’t make it false or fabricated. As Elizondo quotes in the book: “It’s not magic. It’s physics.”

I listened to this as an audiobook, and I found myself audibly talking back to it: “What’s the motive of their visits?!” (He addresses this big question, and it’s fascinating.) Elizondo also dives into the UAP focus on nuclear power, the military, and water, as well as the urgency in contemplating national security concerns presented by these phenomena, inviting us to reassess our own concepts of humanity and consciousness. I long to know more about the sociological dynamics of these beings and their culture. Do they visually distinguish themselves? How do they communicate? Are there subcultures? What do they think of us? Evidence points to their exceptional intuitive properties — are they more evolved versions of us?

The bipartisan legislation that was recently passed to further collect, investigate, and make public the incredible volume of evidence that — until recently — has been largely buried and ignored lends more credence to and hope for what we may eventually uncover about “our friends from out of town.” This book is sober, scientific, and riveting. Read it and let’s discuss.

I also highly recommend all of the terrific books I read and reread by my recent guests: Vote With Your Phone by Bradley Tusk (our convo here); Connected by Nicholas Christakis (our convo here); Modern Friendship by Anna Goldfarb (our convo here).

Exhibitions

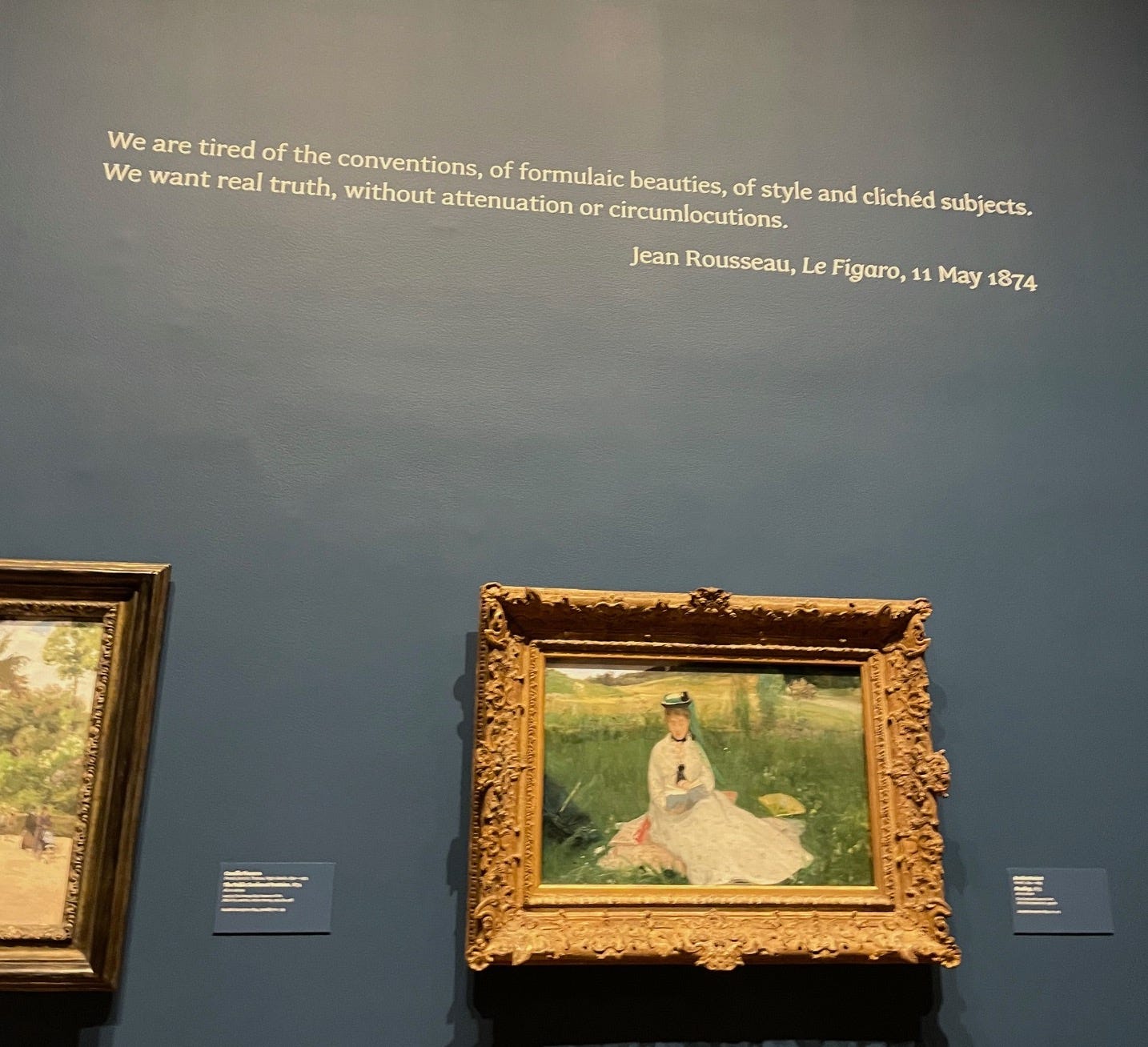

Salon 1874: The Impressionist Moment is currently exhibiting at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. Like Secessions, which chronicles the movement that took place in Berlin, Munich, and Vienna a few decades later (and which I wrote about in Vol. 1), Salon 1874 also looks at moments when art rebelled against art — or, more specifically, art as a rebellion against the status quo. Just like fashion and other forms of creative expression, art can take on a conformist quality and be restricted by powerful institutions. There is safety in conformity. But the impressionists, like the secessionists, believed art was no place for comfort, striving for freedom at any cost.

Roads Not Taken. Or: Things Could Have Turned Out Differently at the Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin

“What if things had been different?” is a question many cultures have contemplated in relation to their most troubling historical moments, but it’s one most pressing for modern Germans. “Roads Not Taken” winds you back in time — beginning with the fall of the Berlin wall in 1989 and reversing to the German revolution of 1848. At several historical forks in the road, the exhibition asks, “What if?” Whether it’s the shot to Franz Ferdinand that began WWI or a the rejection (twice) of an aspiring young artist named Adolf Hitler to the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, it’s easy to forget that one person’s actions or experience can be the spark that ignites world-changing wars and movements — for better or worse. (Revisit my conversation with physician and sociologist Nicholas Christakis for the science behind the network effect.)

Music

I leave you with this song by one of my favorite contemporary bards, Van Morrison: “Why are you on Facebook?” It came out a few years ago, but I only recently discovered it, and in addition to making me laugh, its lyrics pose some contemplation-worthy questions. Feel free to weigh in on whether you agree with Van in the comments:

Why are you on Facebook?

Why do you need second-hand friends?

Why do you really care who's trending?

Or is there something you're defending? /

Get a life, is it that empty and sad?

Or are you after something you can't have?/

Did you miss your 15 minutes of fame?

Do you not have any shame?

Or is it some kind of twisted game?

Why are you on Facebook?

I also listened to Imminent while on a road trip. I will admit that I slept through big chunks of it, but my husband, who is a huge skeptic, listened to the whole thing. He came out with a healthy respect for Elizondo and the book. He is no longer a complete skeptic and is curious about what the government's next steps are. I am also curious about the sociological aspects of these beings and felt that Elizondo's book lacked this aspect of investigation. Thanks for all bringing this book up.

FELICES Y GRACIAS THE SOCIOLOGY OF EVESYTHING